Tespr

Teh-spur

Tespr are a very large subterranean insect species hailing from the planet Xilxixian. It isn’t clear when or how tespr were introduced to Serpentis but scientists suggest that the initial infestation may have been spread via spore-ridden space material. Tespr on Serpentis are predominantly found in the glacial ring bordering the High Mountain Ridge and tundras. There are noticeable differences between the tespr of Xilxixian and those of Serpentis. Tespr are close relatives of the largest Xilxixian creature known as the Kizinkorzik.

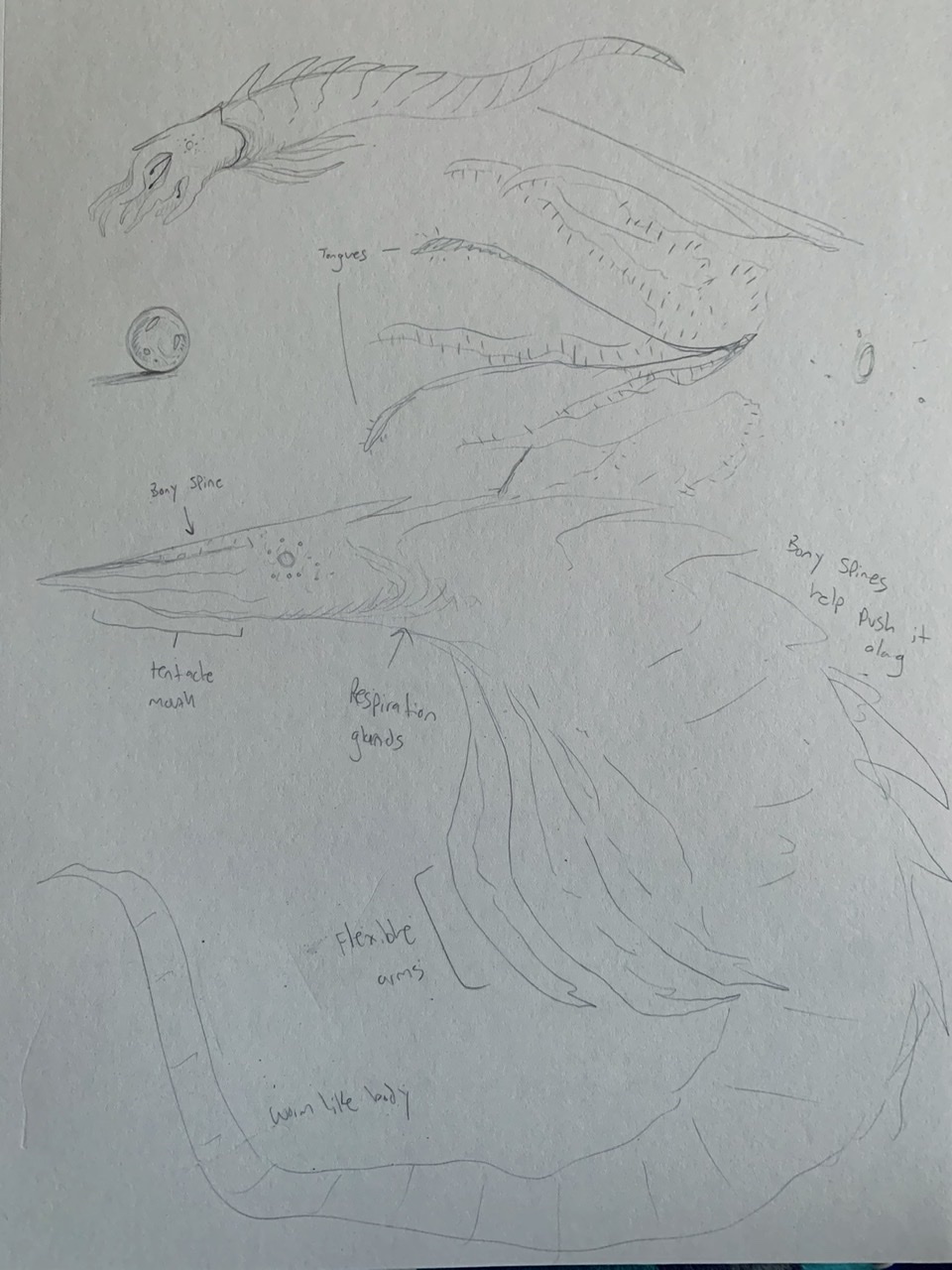

Akin to fish gills, tespr have respiration glands just behind the lower jaw that allows the creatures to breathe through the carapace. Along the back, these insects have plated spines that allow the creature to become mobile underground by pushing them along. In addition, they have six long flexible arms which grapple onto surfaces. The arms are used for underground movement typically but can also be used to pull its body along above ground. They are not capable of lifting the creature fully off the ground due to the angle at which the legs are positioned on the body.

Just like any other insect, tespr will molt as they age and grow. They often take refuge in empty brooder dens or isolated pockets during the process. Once molted, it will take a few days to a few weeks for their new exoskeleton to harden. During this time they are vulnerable and some luckless few may be fated at the hands of another tespr or a hungry group of Serpentians. Tespr come in a variety of colors, although most are muted or muddied reds, browns, greens, or blues. Some that spend their lives in glacial stretches may take on more vibrant colors. Their rough exoskeletons are often blotched with lighter or darker tints and shades of the base color. Tespr flesh is grayish white but will turn pink or red when cooked.

Tespr burrow and create extensive tunnel networks. They have an excellent sense of direction and memory. It is suggested that tespr maintain a mental map of the tunnels and burrows which allows them to return to the same brooder den for egg laying, take favored routes, avoid potentially dangerous routes, and establish favored hunting grounds. Tespr are only able to travel forward due to their legs’ range of motion.

These invertebrates will eat anything that will fit in their mouth or isn’t bigger than them and are not opposed to consuming members of their own species, particularly juveniles, larva, or even an injured or deceased adult.

Because tespr live in colder regions, their metabolisms are slow. They surface only to feed and will typically rest somewhere for weeks after consuming a large meal.

Despite being exclusively subterranean, tespr do sport eyes and have quite a few of them. They possess one large eye on either side of their head surrounded by a plethora of smaller eyes. These eyes are quite primitive and are poorly suited to seeing much of anything. However, because there are so many, the tespr’s eyesight is passable, but not something it relies on. Visual sight is more handy when looking at prey from above ground than anything. Some scientists suggest that tespr may become totally blind in the next few thousand years. Tespr may have had better eyesight somewhere down the line, but that requires studying a Xilxixian tespr which are not easily accessible.

A female can lay up to some six thousand eggs in one brood, although over a quarter of those are infertile and used as the initial food source for larva that hatch. Tespr may reproduce once each season, triggered by the changing of the temperature, but eggs are significantly fewer in number in the warmer times compared to the large clutches produced in the winter. Neither parent cares for the young.

Larva are weak, soft skinned, and very vulnerable upon hatching. Those that hatch first and harden their skins the fastest (this process may take weeks) are often those that survive the gauntlet of cannibalism in the brooder den. Less than a hundred may leave the den, but even fewer survive to adulthood. This intense period of cannibalism is successful because it ensures only the strongest survive and provides a steady supply of food for the young to build up size and strength prior to the few survivors being released into the world. The process is also a natural population control. Once the larva reach juvenile size, they will leave the den and begin their struggle into adulthood.

Popular uses of tespr include chopsticks and armor made of its carapace, dried or cured meat products, pickled eyes, steak, brined eggs, and Ebelu Tii Tespr. Other products include kitchen or dining utensils, storage containers (made from the eggs or carapace), decorative items, or even furniture and textiles.

Tespr are always harvested from the wild. Tundra Dwellers often keep record of the tespr they see in their area and document their movements each season. An adult tespr would feed a family for weeks, but adult tespr are often left be so they can breed and produce the highly prized eggs and larva. Adults are also much more trouble to deal with, although molting adults are typically an opportunity too perfect for Serpentians to resist. Tespr may produce hundreds or thousands of eggs in a single season and are considered a sustainable food source if harvested responsibly. Many Tundra Dweller homesteads keep track of brood burrows and time their arrival with when eggs are just beginning to hatch. Freshly hatched larva are vulnerable, soft, and easy to transport. Tespr, for large scale consumption, are pulled from their brooder dens as eggs or newly hatched larva and placed in nurseries where they are grown to a desired size prior to processing.

Since the commercial harvests of tespr eggs and larva, tespr populations aren’t what they once were. This has eased the pressure from destruction of habitat and drop in Serpentian populations. Because tespr numbers are kept in check, tespr offer a number of benefits: food for Serpentian people and animals, hideaways for burrowing creatures, and population control of species that would otherwise lend a hand to disrupting habitats or prey on Serpentian people.

Biology and Physiology

Appearance

Tespr are the largest known invertebrates found on Serpentis. Their bodies are long and wormlike with a hard carapace that is thicker across the front half of their form. The head is triangular with a tough bony spine jutting from the snout which supports the shape of the tentacle appendages that make up its mouth. Tespr have quite a few primitive eyes that are encased in a clear shell which protect their sensitive eyes from damage when moving beneath the surface.Akin to fish gills, tespr have respiration glands just behind the lower jaw that allows the creatures to breathe through the carapace. Along the back, these insects have plated spines that allow the creature to become mobile underground by pushing them along. In addition, they have six long flexible arms which grapple onto surfaces. The arms are used for underground movement typically but can also be used to pull its body along above ground. They are not capable of lifting the creature fully off the ground due to the angle at which the legs are positioned on the body.

Just like any other insect, tespr will molt as they age and grow. They often take refuge in empty brooder dens or isolated pockets during the process. Once molted, it will take a few days to a few weeks for their new exoskeleton to harden. During this time they are vulnerable and some luckless few may be fated at the hands of another tespr or a hungry group of Serpentians. Tespr come in a variety of colors, although most are muted or muddied reds, browns, greens, or blues. Some that spend their lives in glacial stretches may take on more vibrant colors. Their rough exoskeletons are often blotched with lighter or darker tints and shades of the base color. Tespr flesh is grayish white but will turn pink or red when cooked.

Habitat

These insects are largely subterranean and almost exclusively found in the colder rings such as the High Mountain Ridge, glaciers, tundra, and highlands. They are particularly ill suited for warmer temperatures due to their heavily insulated bodies adapted for absorbing heat rather than releasing it. They would effectively cook within their own shells. It isn’t known whether tespr can survive in the Dark Zone.Tespr burrow and create extensive tunnel networks. They have an excellent sense of direction and memory. It is suggested that tespr maintain a mental map of the tunnels and burrows which allows them to return to the same brooder den for egg laying, take favored routes, avoid potentially dangerous routes, and establish favored hunting grounds. Tespr are only able to travel forward due to their legs’ range of motion.

Diet and Hunting

Tespr feel the vibrations around them as they travel and hunt. They use these vibrations to make conclusions about what may be food and what may be a threat. Tespr will usually ambush prey by appearing just beneath the victim and ensnaring it in its deadly jaws. It may also surface near the victim and use its trio of long tongues to lasso the prey item and pull it to its doom. Tespr will periodically use its head spine to impale large prey items to reduce the likelihood of injury to itself.These invertebrates will eat anything that will fit in their mouth or isn’t bigger than them and are not opposed to consuming members of their own species, particularly juveniles, larva, or even an injured or deceased adult.

Because tespr live in colder regions, their metabolisms are slow. They surface only to feed and will typically rest somewhere for weeks after consuming a large meal.

Sensory

Use of vibrations and touch are a tespr’s primary tool to navigate the world around it. Tespr lack a sense of smell, and, while they lack a conventional sense of hearing, they are capable of feeling vibrations produced from sounds such as voices, footsteps, music, etc. Their bodies are lined with glands that allow them to detect these vibrations. Because tespr produce their own noises when traveling, they will pause to “listen” to sounds around them. At a young age, tespr will approach anything of interest, but as they age, they begin to recognize patterns based on the subtle differences in vibrations that come from particular sources. It is believed that tespr can taste with their mouthparts and tongue, as well as the soft parts of their exoskeleton, maybe even their entire bodies. Their sense of taste is largely used to detect the chemical trails of passing tespr which allow them to pass bodily information to one another such as age, health, and reproductive status.Despite being exclusively subterranean, tespr do sport eyes and have quite a few of them. They possess one large eye on either side of their head surrounded by a plethora of smaller eyes. These eyes are quite primitive and are poorly suited to seeing much of anything. However, because there are so many, the tespr’s eyesight is passable, but not something it relies on. Visual sight is more handy when looking at prey from above ground than anything. Some scientists suggest that tespr may become totally blind in the next few thousand years. Tespr may have had better eyesight somewhere down the line, but that requires studying a Xilxixian tespr which are not easily accessible.

Temperament

It is also speculated that each tespr leaves a chemical trail which communicates to other tespr who has been where and what stretches of territory belongs to who. This allows tespr to avoid another’s territory and prevent aggressive conflicts. These creatures are incredibly territorial and will happily consume one another given the opportunity. Males will often gather in numbers when a receptive female is detected and aggressive encounters are almost unavoidable. Males will use their head spines to joust and injure one another until a winner is determined. The loser is usually eaten if it doesn’t escape. Either gender will fight similarly outside of mating activity.Intelligence

Tespr are quite intelligent creatures. They make mental maps of the tunnel systems they’ve built or been through and can even remember exactly where a favored brood chamber or hunting ground is and how to get there. These insects can also recognize patterns formed based on the types of vibrations that come from particular sources. For example, they recognize the vibrations of a fellow tespr off in the distance, the feel of rain hitting the surface above, and the vibrations produced by a particular type of animal. This allows the tespr to conclude whether something is worth chasing as prey, avoiding as a threat, or ignoring all together to conserve energy. Tespr are not sentient and are not capable of thought, reason, or speech.Reproduction

Unlike the Xilxixian variety which is believed to reproduce with spores, Serpentian tespr are egg layers and reproduce sexually. Eggs, which are spherical and glasslike, are lain in large underground burrows close to the surface or in pre-existing caves and air pockets. It is believed that chemical trails indicate whether females are receptive. Females will hole up in burrows as they wait for the arrival of a male. The male will coil around the female and wrap her in his spindly limbs while copulation occurs. Mating can take several hours.A female can lay up to some six thousand eggs in one brood, although over a quarter of those are infertile and used as the initial food source for larva that hatch. Tespr may reproduce once each season, triggered by the changing of the temperature, but eggs are significantly fewer in number in the warmer times compared to the large clutches produced in the winter. Neither parent cares for the young.

Larva are weak, soft skinned, and very vulnerable upon hatching. Those that hatch first and harden their skins the fastest (this process may take weeks) are often those that survive the gauntlet of cannibalism in the brooder den. Less than a hundred may leave the den, but even fewer survive to adulthood. This intense period of cannibalism is successful because it ensures only the strongest survive and provides a steady supply of food for the young to build up size and strength prior to the few survivors being released into the world. The process is also a natural population control. Once the larva reach juvenile size, they will leave the den and begin their struggle into adulthood.

Influence and Distribution

Tespr are a major staple of many Serpentians’ diets. The Tundra Dwellers are known for their discovery of tespr as a viable food source and instilling them in the planet’s food culture. Thanks to the Shyr and the planet’s love for bug meat, the tespr population quickly dropped and stabilized. They eventually settled into their own ecosystem niche.Popular uses of tespr include chopsticks and armor made of its carapace, dried or cured meat products, pickled eyes, steak, brined eggs, and Ebelu Tii Tespr. Other products include kitchen or dining utensils, storage containers (made from the eggs or carapace), decorative items, or even furniture and textiles.

Tespr are always harvested from the wild. Tundra Dwellers often keep record of the tespr they see in their area and document their movements each season. An adult tespr would feed a family for weeks, but adult tespr are often left be so they can breed and produce the highly prized eggs and larva. Adults are also much more trouble to deal with, although molting adults are typically an opportunity too perfect for Serpentians to resist. Tespr may produce hundreds or thousands of eggs in a single season and are considered a sustainable food source if harvested responsibly. Many Tundra Dweller homesteads keep track of brood burrows and time their arrival with when eggs are just beginning to hatch. Freshly hatched larva are vulnerable, soft, and easy to transport. Tespr, for large scale consumption, are pulled from their brooder dens as eggs or newly hatched larva and placed in nurseries where they are grown to a desired size prior to processing.

Invasive Ecology

The first appearance of tespr resulted in lowered populations of native wildlife and Serpentians (particularly Tundra Dweller Shyr ), as well as large scale destruction of the cold-region environments due to the insect’s subterranean existence. Extensive burrows and tunnels eventually collapse, causing large scarring across the glaciers and tundra fields, development of sinkholes, deforestation, and loss of habitat. These tunnel collapses have also altered river patterns, drained lakes, and disrupted underground aquifers.Since the commercial harvests of tespr eggs and larva, tespr populations aren’t what they once were. This has eased the pressure from destruction of habitat and drop in Serpentian populations. Because tespr numbers are kept in check, tespr offer a number of benefits: food for Serpentian people and animals, hideaways for burrowing creatures, and population control of species that would otherwise lend a hand to disrupting habitats or prey on Serpentian people.

Origin/Ancestry

Xilxixian

Conservation Status

Invasive / Regulated

Average Length

26+ feet

High Mountain Ridge

Glaciers

Tundra

Highlands

Tespr Products

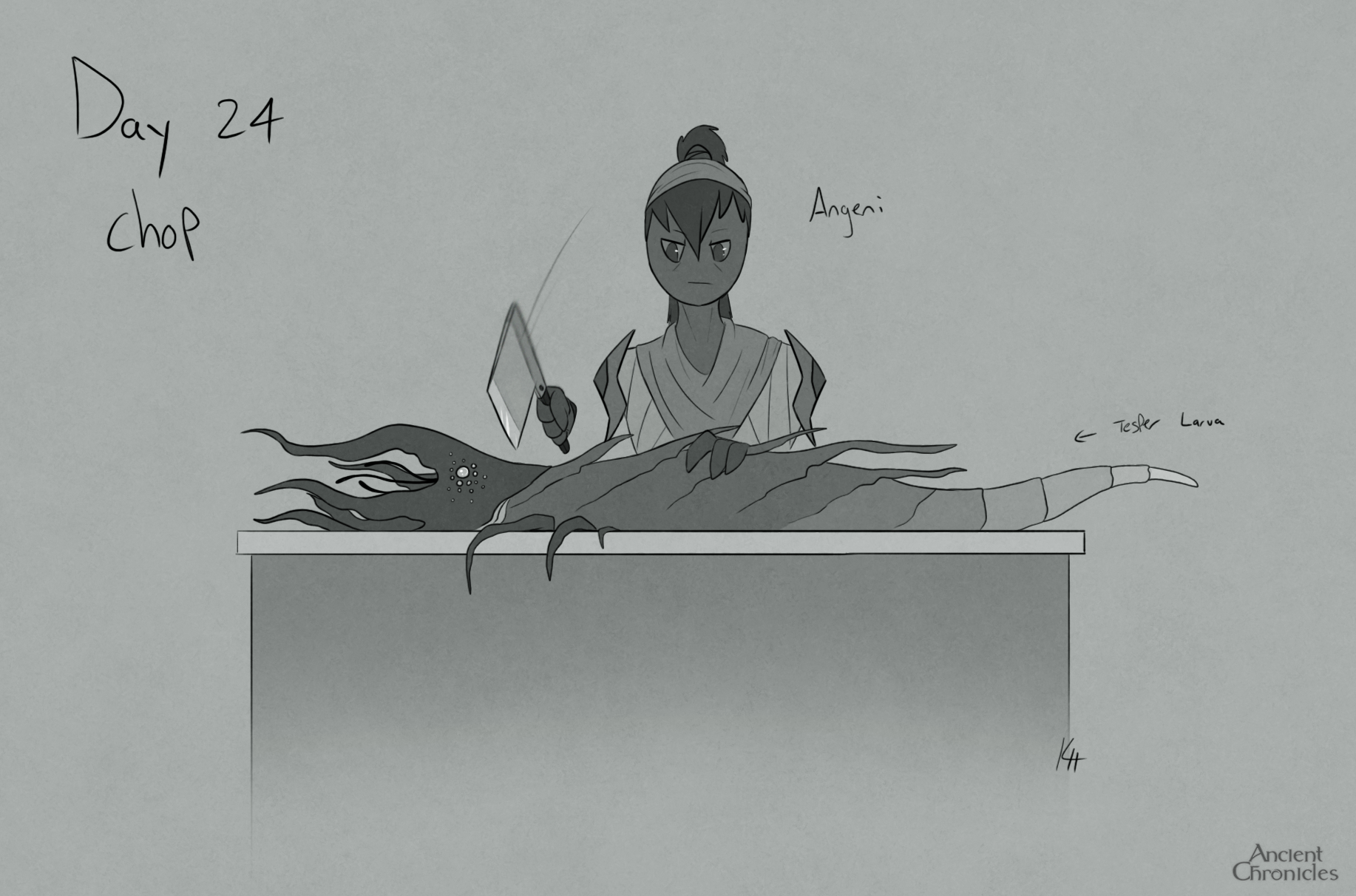

There are a variety of products tespr are known for such as chopsticks, armor, furniture and textiles, storage containers, kitchen and dining utensils, and decorative items. Food items include dried and cured meats, pickled eyeballs, steaks, fillets and other meat cuts, sushi, brined eggs, and Ebelu Tii Tespr. A Tundra Dweller Shyr preparing a tespr larva for Ebelu Tii Tespr

Comments