Angjao is the traditional religion of the

Hingen people of

Liang.

Angjao has a long history, and it has in some form been an intrinsic part of Liang's society for thousands of years. The religion has no founder, and evolved fluidly alongside the culture and people of the island empire. It's form today is a product of this long process, wherein it adapted to social and governmental demands.

Beliefs

Angjao effects many parts of Hingen culture. The core beliefs of Angjao are informal, and there is no holy book.

Various scriptures and poems attributed to ancient priests or the words of spirits are interpreted at the will of priests and believers. It is a religion that places innate spiritual qualities in all things.

The sun, the moon, the grass below our feet, the water we drink. Give thanks for the deer you eat, and the grain that grows for you. These things are given to us by the Peh.

Spirits called

Peh (p-eh) inhabit most things. Trees, rocks, grass, waterways, and items of importance (generally antiques). Gods (Pele) are the most important of the Peh, determined somewhat abstractly based on popularity and the importance of their aspect.

The religion is formally led by the

Shen, who is also the head of state of Liang. He has little oversight over actual worship, but acts as the chief priest of the worshipers of

Ochino, the Pele of the island and most important figure in Angjao religion.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is an important tenet of Angjao belief system. A pyramid of reincarnation is followed by the Angjao's believers. Charitable and good people will rise up as they reincarnate, living as more important people in their next life, usually their own descendants.

The evil are the result individual failing, and the bad people in life will remain static, unable to progress or go backwards. To overcome a history of static upwards mobility in your family is considered a great achievement. Therein, upwards social mobility is the ultimate goal of a well lived life. Due to this, the Shen is considered the pinnacle of achievement as a mortal. Yet to be Shen is not the end goal; a good Shen, who lives wisely and rules well, may reincarnate into a spirits or magical creatures who will watch over the Liang state.

Death is the slow sapping of your soul to the next generation, the soul moving into your children or descendants as they grow old. A long life with many children means a powerful soul.

Taboos

There are not particularly many taboos in Angjao belief. Among them are insulting a Peh or Pele and praying to your Peh in the temple of another Peh. Discussing sex, marriage, or bodily functions within a temple's grounds is also forbidden. It is tradition to leave foot and head coverings at the door of a temple, as a mark of respect.

Outside of in relation to temple etiquette, Angjao believers generally hold to codes of conduct that may be set by their local priesthood. This means that taboos are often deeply regional, and rooted in ancient times. The shrine of a small farming village may forbid the harming of beasts of burden, or the shrine of a fisher Pele may forbid sailing during storms. Sometimes, these may sound practical and the root reason be easy to understand, but over time, some have become obscured in tradition and changed till their original purpose was lost.

Worship

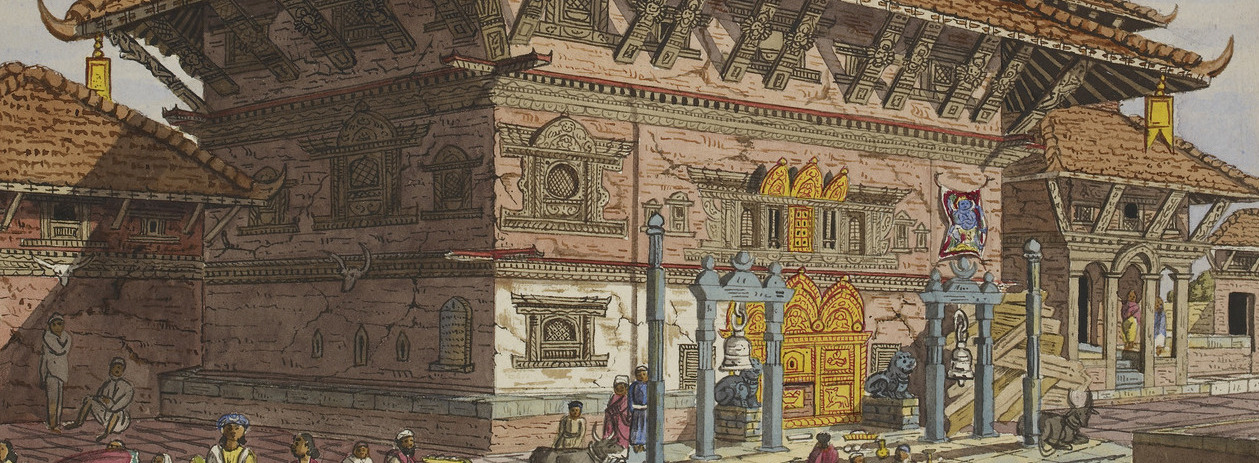

The shrines of Angjao are often informal. Shinres will be dedicated to a local god or spirit/Peh, usually a manifestation of significant local features (a mountain spirit in an alpine village, a sea god in a fishing village). The priests of these temples are employed by offerings from the local area.

In small villages, a shrine may be maintained only by a part-time volunteer priest, who has another profession, or be maintained by a village widow or elder. Priests may marry, and sometimes shrines become a family legacy, with generations continuing to maintain it.

Towns of a notable size may have many shrines of varying size, and cities may be overflowing with shrines on every street, ranging from great temples patronized by the nobility, to humble shrines.

There is no requirement to be a priest, except the approval of whatever priest acts as chiefcustodian of a particular temple. Yet the largest may have dozens or even hundreds of priests dedicated full time to their maintenance, and form entire organizations, with formal training and subsidiary shrines.

In addition, many homes may have a small shrine to gods relevant to the family, such as a spirit of craft in the home of a weaver, and merchants may keep a statue of a spirit of luck or wealth in their shops.

Choosing your Peh

Each believer is generally considered to belong to one Peh. This is not to say that thanks can't be given to any other Peh, but there is one Peh to whom each soul owes their greatest worship, and in return receives guardianship from. Peh are usually familial or related to one's career or talents. Generally, until leaving home to find work, worshipers follow the Peh of their parents, or mother if they vary. Yet upon joining a workplace, the worshiper will traditionally adopt the Peh of their profession.

Where professions are not particularly organised, a worshiper may chose a Peh due to where they live or stay with their families Peh. Later in life, individuals generally drift to Peh that hold importance to their life be it philosophical concepts, important beliefs, their work, family, living place or other aspect.

In prayer, one will usually pay respect to their own Peh, the minor spirits of household objects and the Peh of their parents, as well as any Pele particular to a prayer they be making - be it love, wealth, healing or good luck. If someone is traveling, they will always pay respects to the Peh of where they are staying, for fear of offending the local spirits.

Festivals

Peh may sometimes be honoured with a festival in their honour. These festivals exist for a number of purposes and on many occasions. They are usually extremely local, and may take place any time in the year. They generally mark important occasions, such as the construction of a shrine, the end of a conflict, or the harvest.

Festivals vary in shape and size. The smallest may be a simple gathering at a shrine, with good food and alcohol and oratory readings. Large and important shrines may host parades, performances, decorate towns, speeches and parties.

Generally, the one connecting aspect of a shrine is the time when the statue of the local Peh is taken out and escorted around the village or city, and then returned to the shrine, where believers leave food and monetary offerings for it, and make requests of the Peh or Pele.

Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage is a notable aspect of the Angjao religion. Believers may make pilgrimages to the greatest temples of their Pele for many reasons. The nobility generally hold that as a rite of passage, young men should travel for a year to many of the important temples of Liang, and learn humility by volunteering with the priesthoods of many beliefs. Others make pilgrimages for reasons besides these. The ill may make pilgrimages to the temple of the Pele of Medicine

Kozue in

Naizen, the shrines of their ancestors Peh, or to local central shrines for regional Peh.

Pilgrimage has become a significant commercial industry in the modern era. Temples market themselves as pilgrimage destinations, hotels are constructed in vicinity of temples to capitalise on pilgrims, and in some cases historical temples have been demolished and expanded to accommodate the influx of pilgrims. The tradition of leaving offerings of money makes this a lucrative prospect for important temples.

I like this religion as a whole. Seems like Shinto and Chinese myth as well as a hint of Buddhism, Are the mthein factor. Am I wrong? Are there any holy men and women? Saints almost?