Freshwater Pebble-Bug

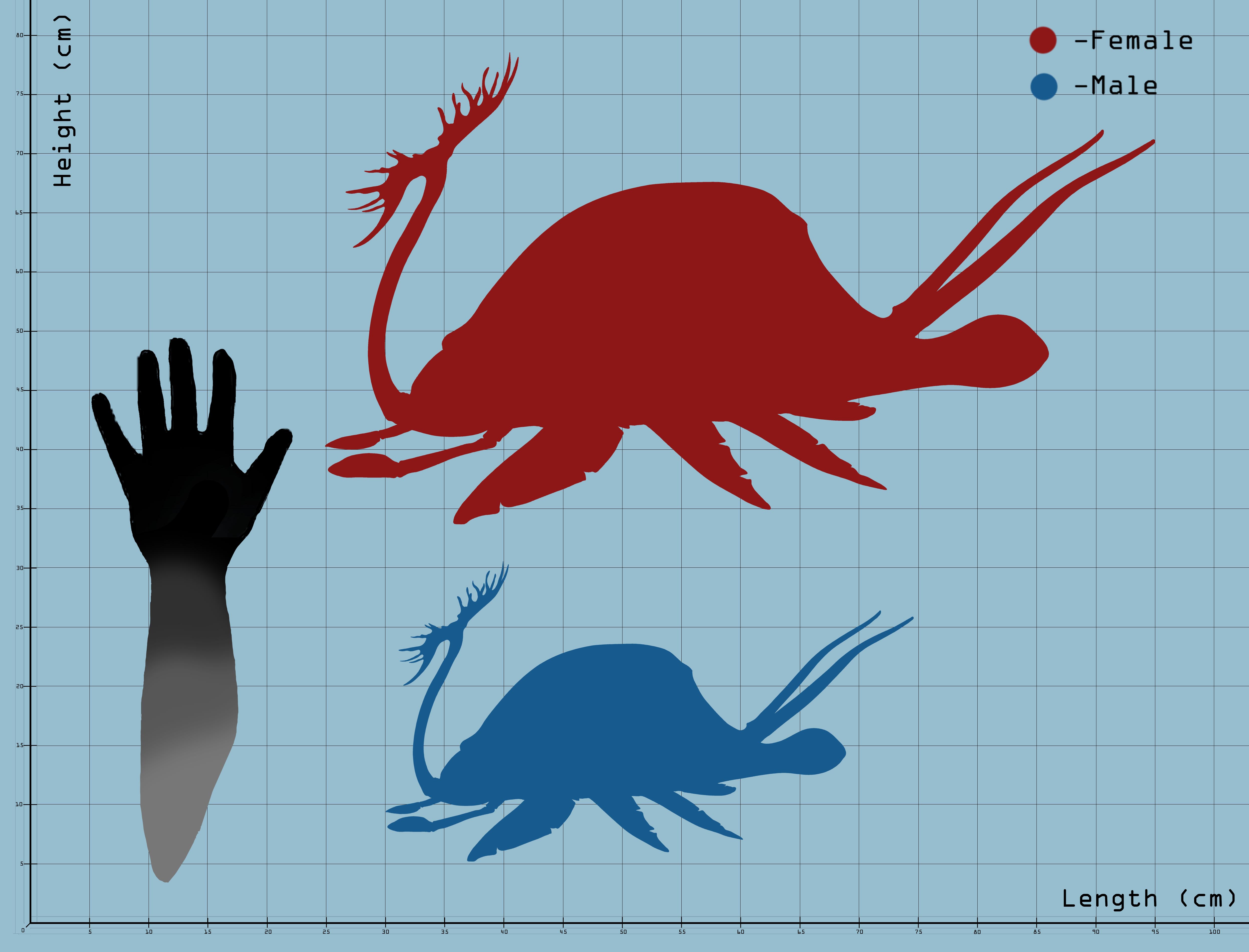

Lapistracon fluvialis is a species of Hoplostracine Gymnocephalid Amphibian from the rivers and streams of the Lizard's archipelago.

Freshwater Pebble-bugs usually live alone or in small groups one near the other, close by to bundles of the model plant they imitate.

The specific shape of the tuberculus mimics perfectly several soft-bodied osteophytes of their native streams, making it difficult to distinguish it from the real thing.

The animal lays on the riverbed among the Cobblestones to conceal itself from prey using its cranial armour to look like the cobbles, keeping the tuberculus open and upright.

This lure attracts herbivorous animals, who will fall directly into the predator's mouth.

The only pair of jaws the pebble-bug possesses end in small paddles it uses to feel the current and possible movements in its general vicinity.

The large eyes are specialized in spotting the faintest trace of movement in the water, making this predator able to notice incoming prey before being spotted, giving it ample time to hide in wait for it to be lured in by the tuberculus.

When prey is close, the Pebble-Bug will quickly dig into the sediment to hide, creating a puff of mud that usually attracts the attention of, getting the fins and head out of sight, a double function that proved advantageous.

Pebble-Bugs are not only found in deep rivers or streams that are active all year, but some of them can also live in seasonal streams, where they'll bury themselves in the mud with the body, allowing them to survive long periods outside of water by breathing the atmospheric oxygen and keeping moist in the soil.

Given the anoxic nature of their hideouts and their seasonality, L. fluvialis adapted to survive long periods in oxygen-deprived environments and outside of water by storing oxygen-rich fluids into the expanded Hydraulic capillary system, which will aid as an oxygen reserve, allowing for longer apnoea periods and keep the skin moist when outside of water.

To help in this second function, the Pebble-Bug will collapse its spinal cords as to fit inside the cranial plastron, which will retain humidity and favour condensation of the liquids transpiring through the skin, helping in water retention, allowing for its continued survival even for months at a time.

Although the animal possesses a row of fins along the body, the creature itself is not able to lift from the riverbed, using them to crawl and dig in the sediment instead.

Very popular pet, the trade for Pebble-Bugs for home aquariums decimated their wild populations as overharvesting of the species both for direct sell and farming purposes enticed many locals to find these animals for some easy pocket money.

Harvesting of the wild populations did not slow down even after local regulations were put in place, leading to the Lizard's archipelago government instituting several protected river areas to ensure the animal's survival in the wild as well as stricter punishments for whoever is found smuggling the species.

Although not illegal to keep wild captured specimens, the TWPP strongly disagrees with the practice, suggesting instead to check for the origin of the animal to make sure it was ethically sourced from established farms.

Basic Information

Anatomy

- Head small and round, eye large.

- Tuberculus Very long and branched in the grappling appendange.

- One pair of jaws ending on a paddle-like structure grow from the post-cranial section of the cephalon, right beneath the start of the cranial plastron.

- Cranial armour composed of only one large curved plate.

- Four pairs of fins run along the length of the body.

- Gill Tail short and stubby ending in a low and rounded Gill Fan.

Genetics and Reproduction

Seasonally monogamous species.

L. fluvialis mates in the summer months, when temperatures are high enough for the egg's incubation.

Nesting behaviour in the species is a bit less intricate than in other members of Palaeostomatosoidea, limiting themselves to small mounds of rocks and the occasional plant cobbled together as best as possible.

Females will come to inspect the nests during their long travel upstream, which usually starts a few weeks before the actual start of the mating season when both mature females and young males will make their way up the rivers.

Depending on the population, egg incubation will happen in two different ways:

-In deep river populations the female will lay her eggs inside mounds of mud to keep them at a constant temperature until hatching

-in seasonal streams, the males will incubate the eggs within their cranial plastron to keep them warm and moist up until they hatch at around the time the water comes back

Young specimens are born very lightweight and will drift in the water column downstream to the more nutrient-rich areas closer to the sea where they'll make their temporary nest in.

One year after birth, the males will migrate upstream alongside the mature females to their final home.

Growth Rate & Stages

Ontogenesis in the species very apparent.

Young specimens have a very thin, almost transparent cranial armours and very large eyes compared to the body.

Natal aculeus particularly dull in the species, gets shed after a few days from birth.

Ecology and Habitats

Freshwater species living in rivers and streams.

They like to live among the cobblestones where they'll hide in, usually among vegetation as well.

Dietary Needs and Habits

Ambush predator that waits on the riverbed in wait for prey species to be lured in by the tuberculus.

They feed on a wide variety of small ichthyomorphs, freshwater invertebrates and pleuropods.

Biological Cycle

Locally seasonal animals.

It will aestivate in riverbeds during the dry season or enter reduced states of activity during periods of prey scarcity.

Additional Information

Social Structure

Lives alone or in small communities, rarely moving around.

They communicate between conspecifics through repeated movements of the fins, creating mud signals.

Domestication

Very popular house pet at the expanse of wild populations.

Always recommended to source your pets from certified farms as to ensure their survival in the wild.

The animal is suitable for intermediate owners, it requires plenty of rock coverage in their tank possibly with plenty of muddy sediment; feed them once every three days.

Uses, Products & Exploitation

Used almost exclusively in the pet trade, it rarely is eaten by local people who would make stews with it, serving them inside of their armour, although now illegal to do.

Perception and Sensory Capabilities

Adeguate eyesight, good hearing.

Symbiotic and Parasitic organisms

In a mutualistic relationship with several species of Pseudonudibranchs that will live on its shell, eating away algae and parasites.

Although these species also live on top of true rocks, they benefit from cleaning the pebble-bugs as the amounts of nutrients on their armour is usually higher than the surrounding rocks.

Scientific Name

Enetodontia; Enetodontida; Paleostomatosoidea; Gymnocephalidae ; Hoplostracinae; Lapistracon; L. fluvialis

Lifespan

35 Years

Conservation Status

Endangered: Although overall populations are healthy, the wild ones specifically have been declining for years; Some laws have been put in place to protect the species

Population Trend: DECLINE

Body Tint, Colouring and Marking

Green to yellow-green body, armour grey with yellow and green fine spotting.

Tuberculus striped in a darker shade, branching mouth tipped in cyan to sea foam color.

Jaws brownish changing to a yellow tint towards the distal end.

Fins striped, countours whitish.

Gill Fan shows a dark grey streak on the lower section.

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

F R E S H W A T E R P E B B L E B U G