The formation of Gnóttvǫllr pass

On the morning of 1544-05-17, the people living along the cliffs of the Gnóttvǫllr pass woke to find their blacksmith and her family in the town square, weeping profusely. All six of them were clearly profoundly affected by something that had occurred overnight and, yet, as they relayed their story in fits and starts, it was clear that the family were suffering from what could only have been some kind of group hallucination.

The smiths insisted that, where there was now a wide tidal inlet running almost the width of the continent, there had as recently as a few days ago been a wide, gently sloping valley filled with sheep and sleepy hamlets. This was clearly impossible: no one else recalled the fields, the cliffs by the shore were worn and weathered, the routes through the pass well-known, and the dangers marked. Twinned beacons stood at Sordurbak and on the promontory east of Snuba, warning ships of the rocks, and had for decades. A doctor was sent for but, although the family had clearly been through some traumatic event, they stuck by their stories. A score of arcanists were sent for, but none were willing to offer a rational explantion for what had happened. The family's compiled account of the days of 1544-05-15/16 are as follows:

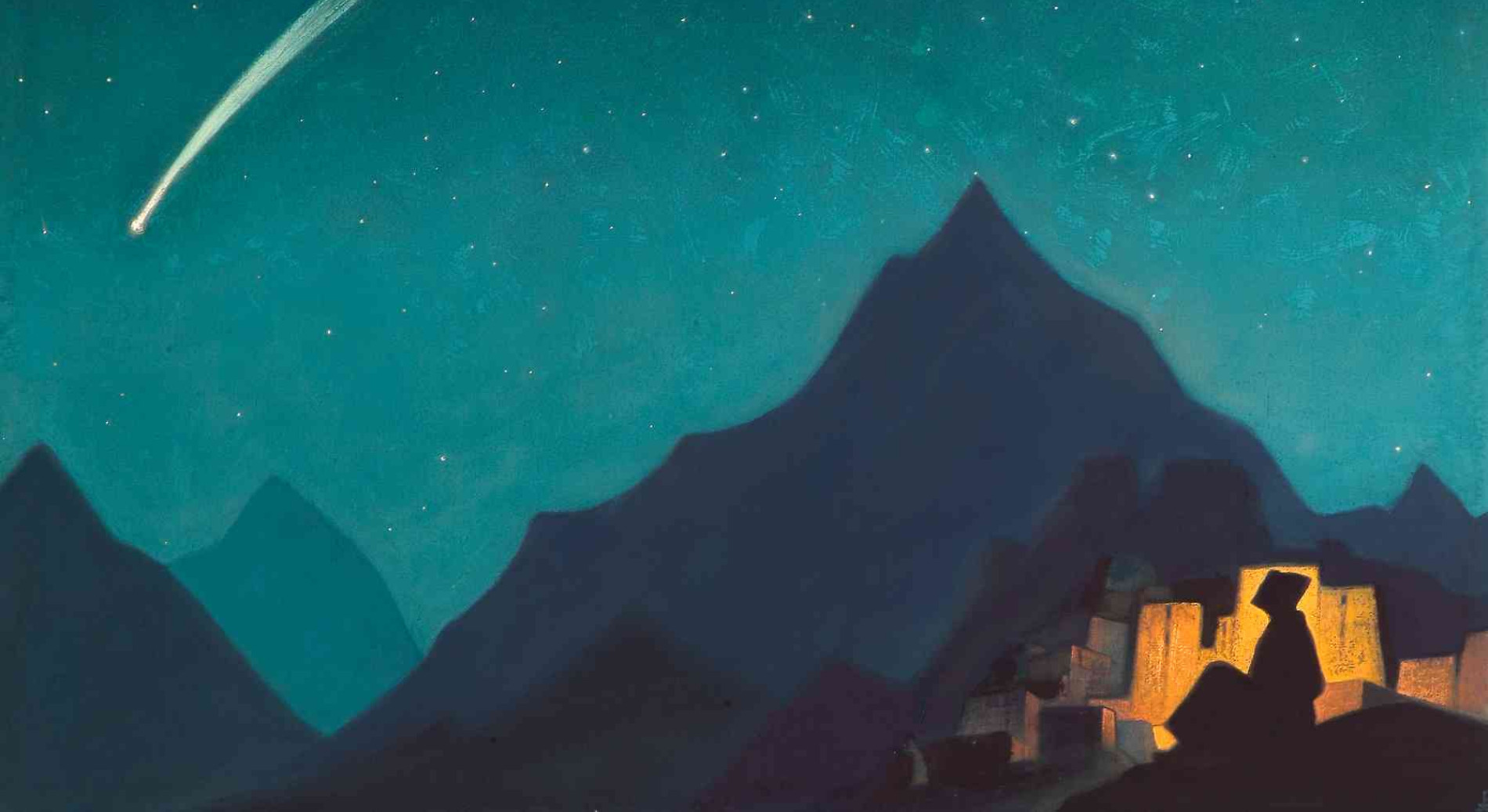

They were awoken the early hours of the morning of the 15th by the sound of a terrible sound - as though the air itself was boiling. The youngest child of the family, Hlátr, saw a shadow "as large as the sky" blot out the moons and the stars for several minutes. The child ran to wake their mothers and the three went ouside together. The smith's wife, Rœða, describes the scene as being as dark as a void, with the only lights being the candles they carried. All at once, a deafening sound, as if if the air being rent in pieces, rang out across the world, leaving the world in the aftermath so silent that the family each belived they had been struck deaf. They saw more candlelights in the village, and ran to them. As they did, the ground began to heave and trees fell and houses collapsed. The young Hlátr was nearly struck by falling masonry and mother Rœða insists that a sizeable bruise she claims was sustained in protecting the child is proof of these events. The smithy remained standing and Megin, the smith, made it known that she believed it to be a magical effect, and that they should gather the townsfolk within the walls and the protection of the iron. To this end, the family were away from the village when the second tremour came, and so were spared death when the earth cracked open, spilling molten rock-iron across the fields and creating what we now know to be the pass. The family and those villagers awake at this point fled to high ground, heedless, in their frenzy, of those left behind. The apprentice, Skipta, admitted this with great shame, and though his mistress gently chided him for such thoughts, it was clear enough to the documentarian that her shame and grief were of equal measure. As the survivors watched, Gnóttvǫllr was torn asunder, a fissure eruption pouring molten rock into the valley and splitting further and becoming wider, "as though a great wedge were driven into the land". The smith and her family, and few people of the village, continued the climb to higher ground as the valley crumbled away into the pass. They watched dawn rise over the blasted pass, and heard a great roaring. Fearing anothe earthquake, the survivors climbed to higher ground, only to watch a great cataract pour into the gap, turning the chasm into the watery pass we know today. The survivors' intention was to leave the valley in search of help but, when the smiths awoke on the morning of the 17th, there was no sign of the cataclysm, nor of the others survivors, who -it transpired - had returned to the village during the night.

Seeing no other options, the smiths returned to the village to find it greatly diminshed from their recollection of a few days ago, but broadly intact barring a few empty houses.

This scenario, if taken as fact, would explain several discrepancies concerning the area:

The smiths insisted that, where there was now a wide tidal inlet running almost the width of the continent, there had as recently as a few days ago been a wide, gently sloping valley filled with sheep and sleepy hamlets. This was clearly impossible: no one else recalled the fields, the cliffs by the shore were worn and weathered, the routes through the pass well-known, and the dangers marked. Twinned beacons stood at Sordurbak and on the promontory east of Snuba, warning ships of the rocks, and had for decades. A doctor was sent for but, although the family had clearly been through some traumatic event, they stuck by their stories. A score of arcanists were sent for, but none were willing to offer a rational explantion for what had happened. The family's compiled account of the days of 1544-05-15/16 are as follows:

They were awoken the early hours of the morning of the 15th by the sound of a terrible sound - as though the air itself was boiling. The youngest child of the family, Hlátr, saw a shadow "as large as the sky" blot out the moons and the stars for several minutes. The child ran to wake their mothers and the three went ouside together. The smith's wife, Rœða, describes the scene as being as dark as a void, with the only lights being the candles they carried. All at once, a deafening sound, as if if the air being rent in pieces, rang out across the world, leaving the world in the aftermath so silent that the family each belived they had been struck deaf. They saw more candlelights in the village, and ran to them. As they did, the ground began to heave and trees fell and houses collapsed. The young Hlátr was nearly struck by falling masonry and mother Rœða insists that a sizeable bruise she claims was sustained in protecting the child is proof of these events. The smithy remained standing and Megin, the smith, made it known that she believed it to be a magical effect, and that they should gather the townsfolk within the walls and the protection of the iron. To this end, the family were away from the village when the second tremour came, and so were spared death when the earth cracked open, spilling molten rock-iron across the fields and creating what we now know to be the pass. The family and those villagers awake at this point fled to high ground, heedless, in their frenzy, of those left behind. The apprentice, Skipta, admitted this with great shame, and though his mistress gently chided him for such thoughts, it was clear enough to the documentarian that her shame and grief were of equal measure. As the survivors watched, Gnóttvǫllr was torn asunder, a fissure eruption pouring molten rock into the valley and splitting further and becoming wider, "as though a great wedge were driven into the land". The smith and her family, and few people of the village, continued the climb to higher ground as the valley crumbled away into the pass. They watched dawn rise over the blasted pass, and heard a great roaring. Fearing anothe earthquake, the survivors climbed to higher ground, only to watch a great cataract pour into the gap, turning the chasm into the watery pass we know today. The survivors' intention was to leave the valley in search of help but, when the smiths awoke on the morning of the 17th, there was no sign of the cataclysm, nor of the others survivors, who -it transpired - had returned to the village during the night.

Seeing no other options, the smiths returned to the village to find it greatly diminshed from their recollection of a few days ago, but broadly intact barring a few empty houses.

This scenario, if taken as fact, would explain several discrepancies concerning the area:

- the name of the pass, Gnóttvǫllr, means 'abundant fields' in the local tongue, but the pass is neither abundant not a field

- several families who have not travelled more than ten miles in any direction have close relatives on the other side of the pass - some fifteen miles by bird's flight and far greater to travel round

- farmers along the edges of the pass own far fewer sheep than would be viable elsewhere and that many of them fell upon hardship in the following years consequentially

- many of the villages and towns along the pass are far smaller than one might expect or lacking fundamental amenities, and became abandoned before year-end

- despite the entire pass and the srrounding area for some five miles around being one of profound arcane inactivity, nearby Hovund boasted one of the largest schools of magic on the continent until 1569, when it relocated to Inveminhe, further inland

Type

Metaphysical, Astral

Remove these ads. Join the Worldbuilders Guild

Comments