Myrrow

The myrrow is genus of a endothermic marine creatures native to the coasts of Osmen, as well as parts of Aresia. Intelligent, bold and charming, myrrow are a popular favourite animal, and play a role in many sea-elf and Osmeni myths and legends.

Description

Myrrow are large, sleek creatures; their size deceptive when you have only seen them from afar. Weighing up to around 55kg during leaner months, females can reach up to 120kg while preparing for pregnancy in Autumn. They can reach 5-6ft in length, and are are about 1.5-2ft tall at the shoulder. The head is long, tapered and almost lizard-like in appearance, with a long forked tongue adding to this illusion. The nostrils are long and slit-like, and can be closed manually for trips underwater. The earholes also possess a muscular "trapdoor" that can be opened and closed at will, allowing the myrrow to cover the ear canal while diving deep underwater, and regulate the ear pressure better. The legs are surprisingly long and more upright in alignment than one might expect of such a creature. This is believed to be a trait of their land-dwelling ancestors, who are thought to have been small, forest-floor foragers on the Azure Isles. Their long legs allow them to clamber across rocks with ease, and flexible wrist joints allow the arms to tuck neatly out of the way while swimming. The toes are webbed, and though most of their locomotion is powered by the hind end and tail, they will often use their paws and legs as rudders to make sharp directional changes underwater. Notably, the hind legs are much shorter than the front, causing an uphill conformation and a strange gait on land. The paws are incredibly dextrous, each toe possessing soft fat pads with rough ridges that grip and conform to the shape of what they are holding, allowing strong grasping without opposable thumbs. Myrrow can range greatly in weight throughout the year, hoarding blubber and becoming quite fat and cumbersome on land when food is abundant and incredibly sleek and lean in harsher months. Their incredibly elastic skin allows for this shape change without resulting in loose skin, which would reduce hydrodynamics in the water. A myrrow pelt can be stretched up to almost 30cm in any direction without losing its elasticity, making it an incredibly valuable resource if tanned and treated correctly. The myrrow's skin is covered in a very sleek, short and dense fur which is difficult to discern from any kind of distance. It lays flat against the skin much of the time, only fluffing up on land to trap air close to the skin and keep the creature warm. Myrrow youngsters, called pups, have fluffy white fur which is much less waterproof than the adults', as they spend much more time on land. The coat of the common myrrow is dark brown-grey, with barred or stripy mottled patterning, and a light underbelly. They are very effectively counter-shaded for the ocean, and blend well into the dark rocks they usually inhabit on land. In Aresia, crested myrrow are more common, sporting more fitting sandy-coloured coats with taller, dark brown dorsal ridges.Evolution

The myrrow are thought to have evolved from a species of ancient, quadrupedal forager on the Western coast of Osmen. Here, the forest met the ocean, and these insect and berry eating foragers slowly expanded to foraging on the coasts as the climate warmed and the forests began to shrink. Overtime, they adapted to foragining in the water on the shoreline, and eventually adapted to swim.Locomotion

Myrrow have incredibly interesting gaits and movement, due to their strange anatomy. Their short but surprisingly upright leg formation means they cannot run splayed like a lizard, and can't run gracefully like a canine. Instead, on land, they adopt a lopey "gallop"; a gait which is not their strongest feature and is only used to escape predators. Because of their awkward running gait, myrrow tend to lounge close to the shore so they can slip into the water if danger approaches- an environment they are much more proficient in navigating. In the water, the limbs tuck neatly out of the way, and the myrrow swims with a sinusoidal motion, primarily powered from the hips and paddle-like tail. The front end of the animal is mostly directional, with the powerful neck and shoulders angling toward the desired direction, and the arms jutted out occasionally to assist in sharp turns. Myrrow can swim at speeds around 15km/h, and up to 20km/h in short bursts.Diet

The myrrow hunts primarily in short-stint dives to the sea floor. They can hold their breaths for up to 10 minutes, and dives usually last between 5-8 minutes. On the sea floor, they will maneuver and turn over rocks and reach between corals to search for prey. They do not tend to hunt for fish, and any fish-eating behaviour is purely opportunistic. The majority of their diet consists of molluscs, crustaceans and marine invertebrates; basically any slow moving creature they can catch with their paws. Their favourite food is the Jasper Urchin, an incredibly large, deep red urchin that is seasonably plentiful in warmer summer months. When tackling urchins, the myrrow will fill their mouth with the spiny creatures, holding them gently so the spines don't peirce their tongues. Once on shore, they tumble the urchins down the rock face so many of the spines are dislodged before attempting to crack them open with their teeth. The myrrow has a selection of sharp, grasping teeth toward the front of the mouth, and large, heavy molars towards the back. These molars are incredibly tough and can crack through most shells and exoskeletons that their claws cannot handle. Despite this, myrrow to throw or bash particularly tough prey against rockfaces to break them open, illustrating their intelligence.Social Behaviour and Reproduction

Myrrow forage and hunt alone, but tend to rest and group in large groups called "bundles". Bundles of myrrow can range from a handful of individuals to huge swaths of sand and rock accommodating hundreds. At times, they will also rest on kelp beds or moving rafts of logs and debris on the ocean, and will be just as comfortable here as on a rockface. Toward the end of summer, females are broken into smaller harems formed by fighting males who will supply their females with food. The females lounge on the shore, gaining weight rapidly as they prepare for their pregnancy. The males, fueled by testosterone, can exhaust themselves to the point of death as they fight, mate and support their harems throughout the autumn. 1-2 pups are born at the very end of winter, and will stay with their mother for two full years. The rapidly growing pups are fed on milk for only a few months they are large enough to start eating their mother's food and begin to learn to forage. Myrrow are incredibly doting mothers, and nurse and protect their young for a relatively long period. This helps keep their population stable despite their relatively low birth rates, and myrrow pups have a fairly good survival rate. Mothers with pups can be incredibly aggressive, and mothers with half-grown pups at foot at the start of breeding season can be just as aggressive as the males pursuing them. The ruthless males are known to quite commonly kill pups from the previous year to bring their mothers into heat once again. Myrrow females with pups in tow are also known to become aggressive toward people, chasing and attacking beachgoers and fishermen. Despite being large and possessing very dangerous teeth and claws, myrrow rarely attack viciously, and are more likely to nip or scream at people to frighten them off, before running back to their bundles."She's as ornery as a whelping myrrow" ~Osmeni idiomMale myrrow are technically sexually mature as early as 2 years old, but females are not equipped to carry pups until around 4 years old. Many young male myrrow are killed in their first "breeding" year, fueled by hormones and picking fights with males much larger and more mature than themselves. Opportunistic hunters often use this period to browse the beaches near bundles and scavenge the bodies of fallen young males. Despite the holes and wounds on their pelts, this skin can still be sold for leather.

Uses

Pelts:

Myrrow pelts are prized for their elasticity and warmth. Though treated pelts are never as elastic as they are on the animal itself or as when they are freshly skinned, properly and gently treated skins are 2-3 times as flexible and stretchy as even the softest calf leathers. This unique property makes their skins incredibly valuable. The skin of pups is even more valuable due to their thick, fluffy fur. A myrrow pup pelt can be sold for as much as 30 Sedian GP or 50 Osmeni Perro. Adult pelts sell for around half the price of pup pelts, but can be very profitable as well treated leathers. In Osmen, Sedia and Virias, there has been an increased push from experts to place myrrow under legal protection. Myrrow skin clothing and goods remain an important symbol of wealth in Virias, and are prized for flexible functional leatherwork in Sedia. In Osmen, as well as many sea elf clans, myrrow skin is an important cultural textile and is required for many religious and cultural objects and dress. Thankfully, recycling old and well cared-for myrrow skins has reduced usage of the leather in part over the last two centuries, but governments remain hesitant to put in any legal protections for the animals.Meat and blubber:

Myrrow are hunted primarily for their skin, but their blubber is an incredibly important food source, mostly in Virias. Myrrow blubber is incredibly energy-dense and melts into a very thick oil that can add calories to any food in winter, as well as effectively pot and seal food. It can be used as a fuel, though this has become much less common since the rise of Flux Energy. Unfortunately, myrrow are known for their foul-tasting meat. Often in Aresia, myrrow are killed for their fur and their meat is left behind and wasted due to this taste. While the blubber is very sweet and palatable, the meat is described as tasting overwhelmingly bitter and almost "burnt" in flavour. It can be slow-cooked over a period of a few days to remove some of this flavour, and in many Osmeni cultures this is followed with a heavy spice mix to cover the remaining taste. Still, it is not a commonly eaten or sought-after meat. Sea elves preserve myrrow meat in brine-jars to use as animal food, as most of their mounts and pets don't seem to mind the bitter flavour.

by Spooktacular

Schollarly name: Myrrow myrrow (common myrrow), Myrrow aresiaris (crested myrrow)

Common name: Myrrow

Conservation: Threatened

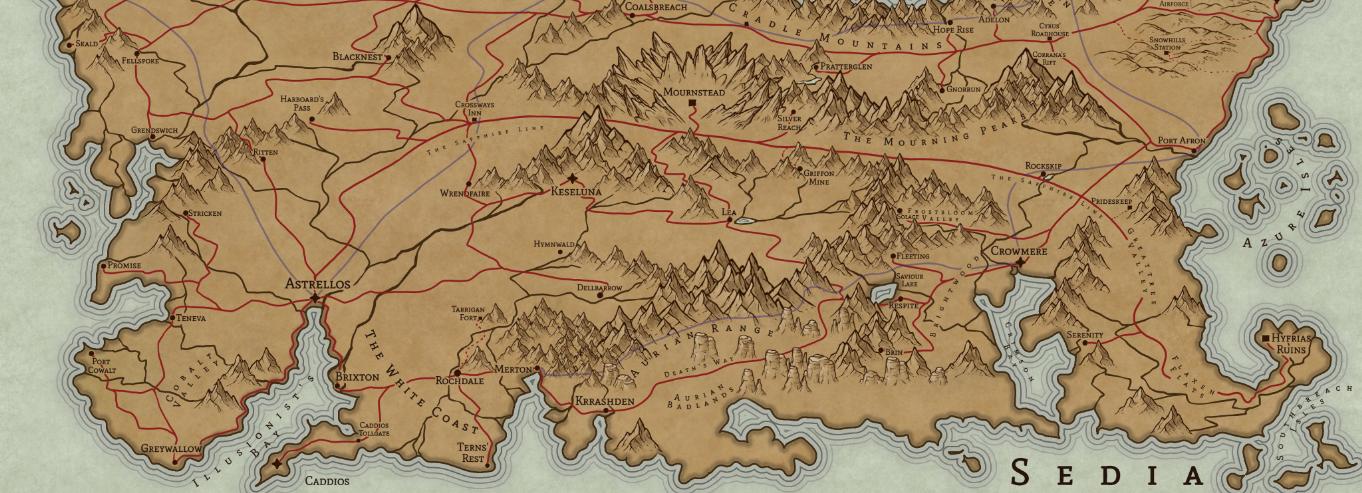

Range: Widespread across coastal regions of Osmen, and found on some coasts in Aresia

Lifespan: 20-30 years

omg i love these guys so much :D I wanna pet one xD

So glad you like them! They're one of my favourite species so far, for sure!