Night of Colour

At last end days of cold

Let the wright work land into spring

Release streams from her hold

May warm winds let bats take to wing

Farewell to the darkness

Now come the days of the sunshine

Let it melt field’s whiteness

So colour again runs like wine.

Ah, she goes at last

Her cruel wind surpassed.

Yen Paean Kiyo was born during the Fourth Reckoning and grew up to become one of the most well-known and beloved poets among the Shilo people. Her poems were primarily about rural life, and have been called "love letters to the countryside". Her personal writings are greatly valued by historians for their detailed descriptions of traditional Shilo life, and her insight into life directly after the Reckoning.

These excerpts from her autobiography detail the Night of Colour festival held across the Shilo Peninsula every year.

These excerpts from her autobiography detail the Night of Colour festival held across the Shilo Peninsula every year.

The Night of Colour

When I was a little girl, my mother told me a story.When winter rolls over the land, she said, there is only one person to blame: the Old Hag. She strikes the ground with her walking stick and ice spreads from its tip across once-green fields. Orange leaves crumble, blue lakes hide beneath blankets of white, and the golden sun is obscured by grey skies. The Hag drains colour, warmth, and life from the land and leaves it barren and white.

But her reign cannot last forever. The seasons turn and the long winter must end. When spring arrives, the Colourwright dances across the land with his brush and bottles of dye to paint the land into spring. He and the Hag sometimes struggle for dominance, with the land going intermittently from white to coloured. The blooming of the white cherry blossoms is the Hag's last hurrah, and signals the true beginning of spring.

History

Look at the dancing fire!

So much fun - now I'm tired

I was six years old the first time we held a proper Night of Colour. Many hundreds of years ago, such festivals were held throughout the land every spring. Father says the ancients began the festival not to celebrate the return of spring, but to beg for it.

The loud music and bright colours were intended to physically drive out the Hag and plead for the Colourwright to arrive. That was when we thought they were deities, before Timilism spread through the peninsula and we abandoned those pagan ways.

As belief in the Hag and the Colourwright faded to fairy tales, the Nights of Colour did as well. It became a "hick" thing, and my father said that by the time he was born, only old-fashioned families still held small, private versions of the festival, and they were thought to be very odd by the others. When the cherry trees bloomed, it was a time to sit quietly beneath them and take in the subtle beauty offered by the Divine.

It was the Reckoning that changed things. The years directly after the Reckoning were very hard; I lost three siblings to hunger, disease, or cold, though I was too young to remember them. Mother says it is a miracle I survived - that I must have absorbed some of the strength of the storm that battered the land during my birth. Six years later, for the first time, my village came to the end of winter with surplus. After the hard winter, they had not just survived, but triumphed. A celebration was in order, so when the old widow Yeogu suggested reviving the Night of Colour, everyone agreed. That first night was so magical to my young eyes that I wrote my first couplet, childish as it may be.

What it would be like to participate in the Nights of Colour of old? How moving such a celebration would be when coupled with earnest belief in the return of the god of spring! To us, the Hag and the Colourwright are figures of superstition, earnestly believed in only by children. In any case, our village held the Night of Colour every year after that, and the new tradition spread to other village through the years. They say it was my poetry that helped popularize the idea far and wide. If that is to be my legacy, I am happy with it.

As belief in the Hag and the Colourwright faded to fairy tales, the Nights of Colour did as well. It became a "hick" thing, and my father said that by the time he was born, only old-fashioned families still held small, private versions of the festival, and they were thought to be very odd by the others. When the cherry trees bloomed, it was a time to sit quietly beneath them and take in the subtle beauty offered by the Divine.

It was the Reckoning that changed things. The years directly after the Reckoning were very hard; I lost three siblings to hunger, disease, or cold, though I was too young to remember them. Mother says it is a miracle I survived - that I must have absorbed some of the strength of the storm that battered the land during my birth. Six years later, for the first time, my village came to the end of winter with surplus. After the hard winter, they had not just survived, but triumphed. A celebration was in order, so when the old widow Yeogu suggested reviving the Night of Colour, everyone agreed. That first night was so magical to my young eyes that I wrote my first couplet, childish as it may be.

What it would be like to participate in the Nights of Colour of old? How moving such a celebration would be when coupled with earnest belief in the return of the god of spring! To us, the Hag and the Colourwright are figures of superstition, earnestly believed in only by children. In any case, our village held the Night of Colour every year after that, and the new tradition spread to other village through the years. They say it was my poetry that helped popularize the idea far and wide. If that is to be my legacy, I am happy with it.

Preparation

Colours flap in the breeze

Driving out the old wizened crone

Flags tied to blooming trees

Warm north wind that's now blown

Sometimes I think I prefer the day before the festival begins more than the festival itself. The anticipation of a plum is always sweeter than the first bite.

The festival begins at sundown, so I always spent the day leading up to it helping the village prepare. I loved to scamper along rooftops and hang brightly coloured flags from the roofs.

The festival begins at sundown, so I always spent the day leading up to it helping the village prepare. I loved to scamper along rooftops and hang brightly coloured flags from the roofs.

When climbing the cherry trees to tie flags to the branches, I pretended I was battling the hag with every blossom I kicked off. Then, when I was still too small to help the men drag in the logs for the bonfire, I hovered around the kitchen and tried to sneak a taste of the treats without Mother catching me. As I got older, I started to help with the cooking itself, and snuck a taste whenever I pleased.

Outside, my brothers and father would drag tables around the bonfire to hold the food. The bonfire would be positioned in a clearing surrounded by cherry trees. One table was always set farther back from the others; this is where the best food would go. I remember Mother fretting every year about hoping to prepare something good enough to be chosen by the community to sit on the Colourwright's table.

It's a bit of a shame that the best food doesn't get eaten, but it must be done. One year, I snuck an apple cake off the table. As an adult now, I know that the Colourwright is only a figure of myth, but I felt horribly guilty that whole night, like I could feel him glaring after stealing his food. At the end of the night, I threw another apple cake into the fire with the rest of the offerings, hoping it would satisfy him.

It's a bit of a shame that the best food doesn't get eaten, but it must be done. One year, I snuck an apple cake off the table. As an adult now, I know that the Colourwright is only a figure of myth, but I felt horribly guilty that whole night, like I could feel him glaring after stealing his food. At the end of the night, I threw another apple cake into the fire with the rest of the offerings, hoping it would satisfy him.

Coloured Lamps

Dazzling colours dance

White trees aflame, shimmering light

We lie below, entranced

My world dims to just us tonight.

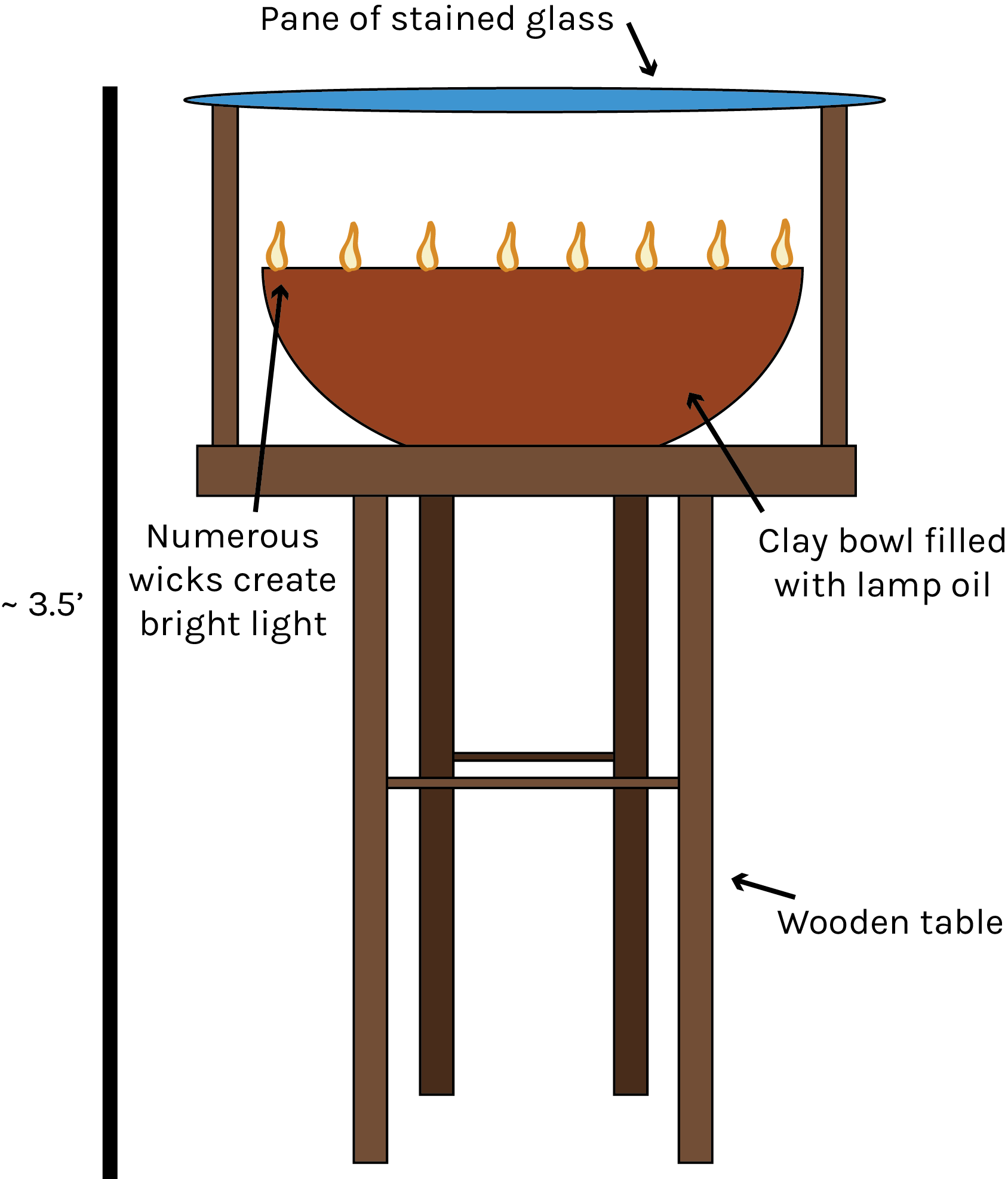

The lamps, I think, are the most special part of the Night of Colour. There are always at least six of them, but I was amazed the first time I was invited to attend the Night of Colour at the royal palace and saw the hundreds of coloured lamps strewn beneath the blossoms. It was like walking through a rainbow that had come down from the heavens.

What a slight against the Hag it is! Her white flowers, turned into a dazzling rainbow by the light shining through thin panes of stained glass below. There are villages, I know, that cannot afford the stained glass panels, or else they have only one or two. There, the trees can only turn orange from the glow of plain fire.

The Festival Begins

Flowers bloom in the spring

Their bright colours allowed at last

But like our dancing ring

Autumn is turning to us fast

As the sun goes down, my heart quickens. At last, it is time. The drums, flutes, and lyres come out and I begin to tap my foot. Songs are sung; I was fifteen when I was first asked to sing my own works, and I had never felt so honoured.

Everyone is dressed in their most colourful clothes, and we circle and spin to the beat around the bonfire. Bright colours flash and whip through the air, and the later it gets, the louder the drums beat. We must be loud - meekness could not drive out a hag so powerful as her!

One year, when I was seventeen, I had to snatch my little brother out of the empty space in the ring of dancers. He only wanted to join, but didn't yet understand that the space was left for the Colourwright. I know the Colourwright is a fairy tale, but it still felt obscene to see him dancing in the space where the Colourwright allegedly danced with us - like walking through a spirit.

Sometimes I wonder if the circling dance is truly the best idea. Of course, the cycles around the bonfire emulate the turning of the seasons, but considering the alcohol involved, I've seen enough dizzy drunks to wonder if we shouldn't allow them close to a bonfire.

The funniest part, of course, is always watching people struggle to decide how to eat. Some foods can be eaten standing, while others you really ought to sit. My old neighbour refused to sit during a festival, though, and once walked around with a scoop of rice in one hand and slices of smoked trout in the other and walked around taking alternating bites! Usually, I prefer to have some stew when the festival first begins, and then stick to kebobs the rest of the night.

One year, when I was seventeen, I had to snatch my little brother out of the empty space in the ring of dancers. He only wanted to join, but didn't yet understand that the space was left for the Colourwright. I know the Colourwright is a fairy tale, but it still felt obscene to see him dancing in the space where the Colourwright allegedly danced with us - like walking through a spirit.

Sometimes I wonder if the circling dance is truly the best idea. Of course, the cycles around the bonfire emulate the turning of the seasons, but considering the alcohol involved, I've seen enough dizzy drunks to wonder if we shouldn't allow them close to a bonfire.

The funniest part, of course, is always watching people struggle to decide how to eat. Some foods can be eaten standing, while others you really ought to sit. My old neighbour refused to sit during a festival, though, and once walked around with a scoop of rice in one hand and slices of smoked trout in the other and walked around taking alternating bites! Usually, I prefer to have some stew when the festival first begins, and then stick to kebobs the rest of the night.

The Morning After

Silence slips over hills

A deep breath before summer's heat

The only sound, birds' trills

Stillness can't delay her retreat.

I once travelled to Taalora and explained the Night of Colours to locals there. The found the morning after the night the most amusing part. From an outsiders' perspective, it does seem rather silly. After our loud music drove her away, we sit in our homes, not raising voices, and not causing commotion, in the hopes that if she wanders back, she won't notice us and keep walking.

Personally, having been present for the first Night of Colour as a child, I'm quite sure this tradition started with very hungover parents wanting an excuse to lie in bed all day and a story for why their children aren't allowed to shout. At least, my father didn't come up with the "she'll come back if we don't lay low" story until I was 8; the first two years had a more typical "be quiet because Papa has a headache" message.

Hengneng:

A style of traditional Shilo poetry, today mostly associated with the poet Kiyo from the years of the Fifth Age. Hengnengs can be 4, 8, or 10 lines long. They are written in stanzas of 4 lines, with a syllable pattern of 6-8-6-8.

10-line Hengnengs have two stanzas of four, followed by a couplet with 5 syllables in each line. The ending couplet is generally marked by an interjection, and creates a final exultation. Hengnengs can be recited, but they are usually put to music and sung.

10-line Hengnengs have two stanzas of four, followed by a couplet with 5 syllables in each line. The ending couplet is generally marked by an interjection, and creates a final exultation. Hengnengs can be recited, but they are usually put to music and sung.

The Night of Colour

Food and Drink

Many delicious foods are prepared for the festival. These are some of the more popular:- Lamb Stew - the Saeka lambing occurs a few months earlier in the year, just in time to make lamb stew for the festival

- Yaudeu - Spicy, fermented potato discs, eaten with rice

- Sherepoi - kebobs with tteokboki (stir-fried rice cakes), potato, pieces of cheese, and chunks of lamb

- Yokhu - fermented milk drink

- Apple Cakes - a type of pancake with a sweet filing of finely-chopped apple and honey

Ogomo by Kristin High

Coloured Lamps

A significant component of any Night of Colour. The lamps are set up below the trees to shine coloured light on the white blossoms.

Primary Related Location

Related Ethnicities

Cover image:

Cherry Blossoms in Seoul

by

Nightfoot