Phylogeny

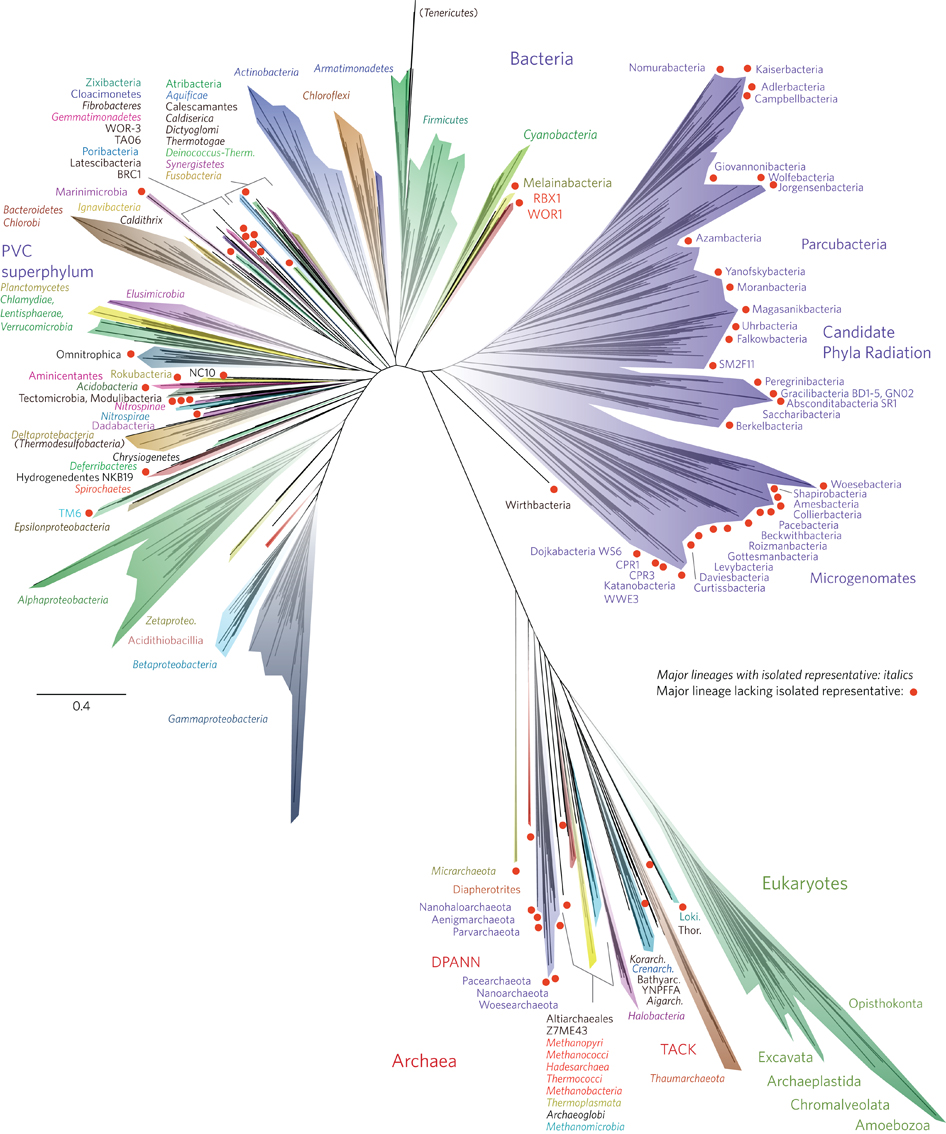

Life in the universe is organized and categorized by biologists into fractal, branching trees, or

phylogenetic trees, according to their evolutionary relationships as revealed by rigorous comparative analysis of morphologies and genotypes. After each split in the branching structure, all organisms which derive from the same branch of the split are considered to be in the same

clade, and many levels of clade have formal names. A sequence of these clade names is often used to describe the general lineage of an organism (its

taxonomy). The

UNH academic community uses a system called

Linnean taxonomy, which is the system used to catalog organisms in

this version of the Omnipedia.

On

Earth, pre-spaceflight scholars only considered formal taxonomic naming up to the level of "

domain," organising all life on the planet into three domains (Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya) linked by an unknown common ancestor. However, when faced with the prospect of lifeforms of completely alien origin, a new formal clade to denote the abiogenetic origin point of a tree of life was added to the taxonomic system. An

arboria, or

genesis group, is a rank above domain intended to separate the myriad trees of life across known space by indicating where their abiogenesis took place. In the cases of panspermia or transpermia, specific notations are used to indicate the phylogenetic points at which the interplanetary migration occurred. The

Terragenia arboria is shown at right, not including the Europan lineages or genetically modified organisms (

source).

Biosphere Classification System

A planet's biosphere, if it has one, has a fairly simple classification system of its own, determined by a few key factors: the origins, basic chemistry, maximum complexity, and predominant environment type.

Origins

Abiogenesis

Abiogenesis is the natural spontaneous development of biology from an abiotic environment. This is not a single spontaneous event; rather, abiogenesis is a process which unfolds over millions of years. Proto-biology gradually increases in complexity in response to certain environmental conditions, starting with the natural formation of complex organic molecules by abiotic factors and proceeding toward self-replication, metabolism, and spontaneous organization into the structures universally recognized as "cells." Several ultra-young biospheres (including

Phanes and

Ninlil) are currently under investigation to better understand the origins of life.

Panspermia

Panspermia is the interplanetary spread of one kind of life from its abiogenetic source world to other places in the cosmos by natural means. Panspermia is a very rare event, documented in an estimated quarter of natural planetary biospheres. In all of these cases the transfer of life occurred via impact ejecta between very nearby planetoids (usually neighboring moons of a larger planet), but transfer of protobiotic chemistry via interstellar comets is also possible in theory. The farthest known panspermic event was the introduction of Terragenia to the subglacial ocean of the

Jovian moon

Europa, across an orbital separation of more than 4

AU.

Transpermia is the interplanetary spread of one kind of life from its abiogenetic source world to other places in the cosmos by artificial means. Spacefaring civilizations tend to bring their native biotopes with them into the stars in some form or other, the most extreme method of which is

terraforming - the process of recreating the homeworld biosphere on another planetoid. The most prolific example of a deliberately transplanted biotope is the

Hemeragenia arboria: the ancient

skgri terraformed nearly a dozen worlds in the two millennia of their interstellar civilization, and about half of these remain populated by hemeragenid life to this day.

Basis

Organic

In the broadest sense, organic life is based on the interactions of carbon and carbon compounds. It is the most common type of life in known space, due to the extreme abundance of carbon, but the versatility of this element results in a vast array of carbon-based biospheres that are nigh irreconcilable with each other.

For example: nanuqgenid organisms have evolved on a

nephelic world with a super-dense, methane-ammonia atmosphere. This environment produced a biochemical system radically different from

terragenids, which evolved on a water-rich

terran world with a mesobaric nitrogen-oxygen atmosphere; however, both trees of life are based upon carbon.

Exotic

The term exotic in the context of biospheres refers to any form of life not based solely on carbon-dominant chemistry. While not nearly as common as purely carbon-based life, a small percentage of the known genesis groups are based at least in part on the elements nitrogen, silicon, and aluminum; each providing unique complex chemistry.

Even within these known bases, there is a considerable extent of structural variation due to environmental diversity, as expected from a sample size of 62 life-bearing worlds. Yet more types of exotic life exist purely as hypothetical concepts: organisms based on heteropolymic acids, lead, plasma helices, and even complex electromagnetic fields.

This sort of biochemical disparity has the potential to cause catastrophic first contact events, though stringent measures have been implemented by the Coaliton

Ecological Research and Preservation Agency to prevent such a disaster.

Protocellular

Protocellular lifeforms are a rare but incredibly varied class of organisms that meet only

some of the criteria for life. This may come in the form of self-replicating

polymers, free

RNA or RNA analogues, or

lipid clusters which perform metabolism but cannot replicate. These first recognizable signs of life are typically found on young, solvent-rich worlds with active suns. Protocellular organisms form extremely simple relationships with each other and their environments, but rapidly develop into more complex forms.

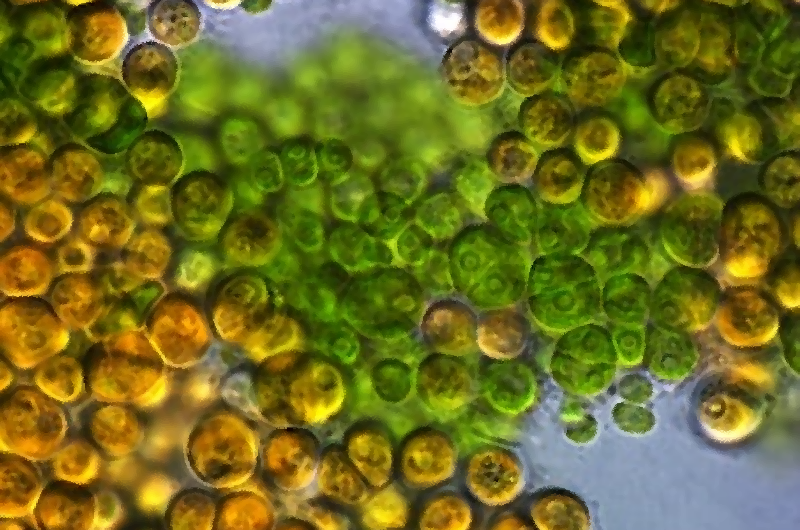

Unicellular

Unicellular lifeforms are by far the most common form of life in known space; however, only about 38% of all documented biospheres are entirely comprised of single-celled organisms. This is not to say that planets with more complex life are devoid of unicellular life; quite the opposite in fact. As the most fundamental and hardiest bio-structure, single-celled life can be found on almost every known

type of planet. Unicellular organisms form fairly simple relationships with each other and their environments.

Multicellular

Multicellular lifeforms are the second most common form of life in known space, although just over half of all biospheres have some form of multicellular life. It is the broadest category of bio-structure, with organisms ranging from

sophonts to Thalassian orbmoss fitting under the multicellular umbrella. This kind of life is only found on older planets whose conditions have mellowed. Multicellular organisms form complex relationships with each other and their environments, giving rise to visible macroecology.

Biomics

Terrestrial

Terrestrial biospheres are a fairly common biomic type comprised of life that primarily dwells on (or, more rarely,

within) the solid surface of their homeworlds. This type of biosphere is found most frequently on

terrae and

aquarae, though some

chionic and

desert worlds have terrestrial life as well. Terrestrial biospheres are typically macroecological as well as microecological, and are one of the more diverse biomic types in terms of biochemistry and evolution.

Marine

Marine biospheres exist solely within liquid solvent on a planet's surface. Marine life is the most common biomic type, of course, being found quite commonly on

oceaniae,

terrae, and

aquarae. However, the line between marine and aerial biomic types is blurred in the cases of supercritical atmospheres such as those on oceaniae and

nephelae, which are something between ocean and sky. Marine life typically resides in water oceans, though hydrocarbon- and ammonia-housed marine biospheres are known to exist.

Subglacial

Subglacial biospheres are characterized by their existence underneath or within the solid icy crust of their homeworlds. This biomic type occurs almost exclusively on

erimae and

chionae, though a few

aquarae have subglacial life as well. This biomic class is most often similar to marine life, as life on cryonic planets typically subsist within oceans. However, subglacial life is distinct in its lack of contact with the sea's surface, as the interior ocean directly borders the ice above it.

Aerial

Aerial biospheres are the strangest biomic type in all of known space, as they are composed entirely of organisms that spend their whole lives airborne; either volant, aerobuoyant, or both. This type of biosphere is only found on

joviae and

nephelae, with the sole exception of the

vulcanic planet

Nuyo in the Gliese 754 system. Because of this, known aerial biospheres are almost always exotic in chemical composition, needing to rely on unusual metabolism to survive in the volatile atmospheres of giant gaseous worlds.

Abundance

Just over 20% of all documented star systems within known space have some form of native biosphere, which is a much greater percentage than scientists of previous ages had anticipated. Many of these systems have multiple life-bearing worlds due to natural panspermia events, bringing the total number of extant, naturally-occurring planetary biospheres to 62.

Biochemistry

Every known biosphere utilizes organic chemistry at least in part, lending heavy support to the theory that carbon is the ideal basis for living systems. The vast majority of biospheres on temperate planets are purely organic, with five cases of organonitrile life; all of these use water as their primary solvent. Biospheres that evolved in temperatures lower than the freezing point of water tend to use organonitrile chemistry and aqueous ammonia instead, though the protocellular life on Ninlil and the microbes of Murray-Callahan reside in lakes of liquid hydrocarbons. Only one high-temperature biosphere has been documented so far: the aerial microbes of Nuyo, which are based on organosilicon chemistry and use sulfuric acid as a solvent. Twelve natural biospheres depend primarily on hydrogen/methane metabolism, two use the sulfur cycle, one (the Ashgenia) uses the iron cycle, and the rest are dependent on oxygen/carbon-dioxide metabolism.

Complexity

Approximately half of all documented cases of abiogenesis have resulted in multicellular life, though studies suggest this may just be dependent on the age of the biosphere –the longer life exists on a world, the more probable the development of multicellularity becomes. Multicellular life is most common on terrestrial worlds, and quite rare on gaseous worlds.

Extinction

While mass extinction events are relatively ubiquitous across life-bearing worlds, there are only two known cases of naturally-occurring biospheres which have gone completely extinct: Indrani and Ashtara. Both of these worlds are moons of gas giants, and geologic evidence indicates they experienced drastic changes in their orbital patterns early enough in their biotic histories to render them uninhabitable to all life. Once life is firmly established on a planet, it is extremely difficult to extirpate all of it. However, it is possible that many biospheres on oceanic or gaseous planets have fully gone extinct, as there is no way to recognize the prior existence of an extinct biosphere without fossils -a phenomenon unique to terrestrial worlds.

Statistics

Instances of abiogenesis

44- Protocellular-stage: 3 (6.8%)

- Unicellular-stage: 17 (38.6%)

- Multicellular-stage: 24 (54.5%)

Instances of panspermia

20- Unicellular-stage: 4 (20%)

- Multicellular-stage: 16 (80%)

Instances of transpermia

37

Statistical breakdown of known arborias

[1] Active molecular metabolism is defined as the intake, internal reaction, and output of chemicals between the environment and the entity in question.

Related Articles

Holy space! This was a beautiful article! I am jealous at how well you can describe the technical and scientific aspects of this article! Its beautifully formatted with some gorgeous artwork too! I would say that this is a great example of a primer article as well. Congrats mate and keep up the great work!